Thrombotic Risk Associated with Inferior Vena Cava Filter Placement in Patients with Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia

Clinical question

Are mortality and thrombotic risk increased in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) undergoing IVC filter (IVCF) placement compared to patients with either HIT or IVCF alone?

Take away point

IVC filter placement did not significantly increase risk of thromboembolism or death in patients with HIT, suggesting IVCF placement may be a viable treatment option for patients with elevated thromboembolic risk secondary to HIT in whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated.

Reference

Moghbel M, Chen Z, Liu C, Rajan S, Vempaty H, and Wang S. Thrombotic Risk Associated with Inferior Vena Cava Filter Placement in Patients with Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021; 32:1629-1634. doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2021.08.025

Click here for abstract

Study design

Retrospective, single-network cohort study of 26 patients with HIT and IVCF placement vs controls with either HIT or IVCF alone.

Funding Source

No reported funding.

Setting

Private hospital network, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, USA.

Figure

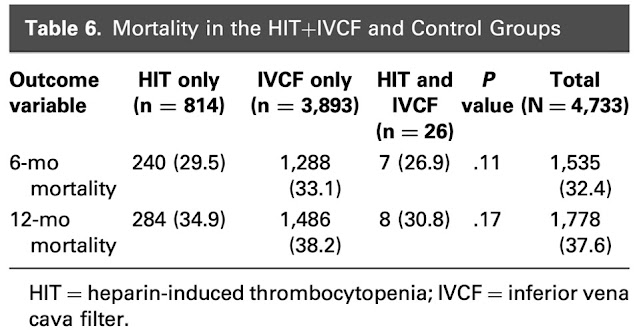

No significant difference in mortality was observed in the HIT+IVCF group versus controls.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is an adverse reaction to heparin resulting in reduced platelet count. Thromboembolic events occur in up to half of patients with HIT. Currently, it is not recommended to routinely place IVC filters (IVCFs) in patients with HIT in whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated due to the paucity of outcomes data in this relatively small population. The authors perform a retrospective cohort study comparing outcomes in patients with HIT receiving IVCFs compared to patients with HIT who did not receive an IVCF and patients receiving an IVCF without a diagnosis of HIT.

Electronic medical records were queried for patients with HIT and/or IVCFs using diagnostic and procedural codes. Patient charts coded with HIT were reviewed manually and excluded if they had been miscoded. The two control groups were unable to be manually reviewed due to the immensity of the sample sizes. Patients in the HIT+IVCF group were stratified into subgroups based on likelihood of HIT (high likelihood = positive serotonin release assay or HIT antibody level >1; intermediate likelihood = HIT antibody level <1) as well as timing of IVCF placement (within 14 days of HIT diagnosis versus >14 days of HIT diagnosis). This 14-day cutoff was chosen based on estimated peak timing of HIT-associated thromboembolic risk.

Primary outcomes were 6- and 12-month mortality and thromboembolic risk, which included new or extended DVT/PE, IVC thrombosis, lower extremity phlegmasia cerulea dolens, and critical limb ischemia. Propensity score matching was performed to control for potential confounders based on demographic data. Comparisons were made using chi-squared and Fisher exact tests.

A total of 4774 patients were analyzed, 26 with HIT+IVCF, 814 with HIT without IVCF , and 3,934 with IVCF without HIT. The most common indication for IVCF placement in the HIT+IVCF group was proximal DVT/PE with contraindication to anticoagulation (n=18, 69.2%).

Mortality rates in the HIT+IVCF group were 26.9% (n=7) at 6 months and 30.8% (n=8) at 12 months compared to 29.5% (n=240) and 34.9% (n=284) in the HIT only group and 33.1% (n=1,288) and 38.2 (n=1,486) in the IVCF only group. No significant difference was noted among groups at either 6 or 12 months (p=0.11 and 0.17, respectively).

Additionally, HIT+IVCF subgroup analyses showed no significant difference in 6- or 12-month mortality between HIT likelihood (p=0.59 and 0.27, respectively) or timing of IVCF placement (p=0.69 and 0.84, respectively). Thromboembolic risk was not significantly different within these two subgroups.

The authors discuss that current guidelines recommend against the routine placement of IVCFs in patients with HIT despite limited comparative data assessing patients with HIT and IVCFs versus either alone. The results of this study suggest that patients with HIT in whom IVCFs are placed are at no higher mortality risk compared to controls nor are they at higher thromboembolic risk compared to previously reported data on patients with either HIT or IVCFs alone.

This study compares mortality rates in patients with HIT receiving IVCFs compared to patients with either HIT or IVCF alone as well as evaluates the thromboembolic risk in patients with HIT receiving IVCFs. The authors note that current guidelines are largely based on data describing high rates of thromboembolic events in patients with HIT in whom central venous catheters or IVCFs were placed, but remark that there is limited data assessing the true thromboembolic risk of patients with HIT and IVCF compared to controls. To that end, this study aimed to more accurately characterize the thromboembolic risk and mortality in this population.

The extremely large sample sizes of the control populations, while advantageous for powering the study, did not allow for manual chart review to ensure that diagnostic and procedural codes were accurately assigned in the electronic medical records. In the HIT+IVCF group alone, 9 out of the original 39 cases (23%) were excluded due to miscoding, which raises concern regarding the accuracy of the HIT and IVCF only groups. Additionally, since the control groups were so considerably large, it was not possible for the authors to review all charts to establish thromboembolic risk in each control group. They rightfully discuss that their thromboembolic risk comparison is therefore restricted to previously published data, rather than having an internal comparison. This introduces potential biases between institutional practice patterns, patient populations, and variability over time.

Although generally quite thorough in the evaluation of the HIT+IVCF group, the authors do not mention retrieval rates of IVCFs in either this population or their controls. Given that IVCFs are known to be associated with greater thrombotic risk if not removed, it would have been interesting to see if timing of IVCF removal had any influence on thromboembolic risk or mortality.

Furthermore, although 6- and 12-month follow up periods are relatively long term in relation to duration of thromboembolic risk associated with HIT (which peaks over 14 days), it may also be of benefit to assess longer (3- or 5-year) mortality rates to validate the conclusions over an extended time period. Lastly, the retrospective design has inherent limitations where a prospective study or randomized controlled trial would offer more accurate comparison, although likely not feasible in this relatively small patient population.

The major strength of this study is its large sample size of patients with HIT receiving IVCFs compared to other studies. Their thorough review of laboratory and clinical data to determine likelihood of HIT diagnosis and timing of IVCF placement adds to the comprehensiveness of the morbidity and mortality evaluation. The scope of their discussion also appropriately addresses the limitations of the data and highlights the need for additional research and external validation.

Overall, this study sheds new light on the question of whether IVCF placement should be considered in patients with HIT in which anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated. For patients with HIT and IVCFs, there was no significant difference in thromboembolic risk compared to rates from other studies nor in overall mortality compared to internal controls. These findings challenge current guidelines that recommend against routine placement of IVCFs in patients with HIT; however, outside validation of these results is essential prior to implementing changes in clinical practice.

Post Author

Catherine (Rin) Panick, MD

Resident Physician, Integrated Interventional Radiology

Dotter Interventional Institute

Oregon Health & Science University

@MdPanick

Summary

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is an adverse reaction to heparin resulting in reduced platelet count. Thromboembolic events occur in up to half of patients with HIT. Currently, it is not recommended to routinely place IVC filters (IVCFs) in patients with HIT in whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated due to the paucity of outcomes data in this relatively small population. The authors perform a retrospective cohort study comparing outcomes in patients with HIT receiving IVCFs compared to patients with HIT who did not receive an IVCF and patients receiving an IVCF without a diagnosis of HIT.

Electronic medical records were queried for patients with HIT and/or IVCFs using diagnostic and procedural codes. Patient charts coded with HIT were reviewed manually and excluded if they had been miscoded. The two control groups were unable to be manually reviewed due to the immensity of the sample sizes. Patients in the HIT+IVCF group were stratified into subgroups based on likelihood of HIT (high likelihood = positive serotonin release assay or HIT antibody level >1; intermediate likelihood = HIT antibody level <1) as well as timing of IVCF placement (within 14 days of HIT diagnosis versus >14 days of HIT diagnosis). This 14-day cutoff was chosen based on estimated peak timing of HIT-associated thromboembolic risk.

Primary outcomes were 6- and 12-month mortality and thromboembolic risk, which included new or extended DVT/PE, IVC thrombosis, lower extremity phlegmasia cerulea dolens, and critical limb ischemia. Propensity score matching was performed to control for potential confounders based on demographic data. Comparisons were made using chi-squared and Fisher exact tests.

A total of 4774 patients were analyzed, 26 with HIT+IVCF, 814 with HIT without IVCF , and 3,934 with IVCF without HIT. The most common indication for IVCF placement in the HIT+IVCF group was proximal DVT/PE with contraindication to anticoagulation (n=18, 69.2%).

Mortality rates in the HIT+IVCF group were 26.9% (n=7) at 6 months and 30.8% (n=8) at 12 months compared to 29.5% (n=240) and 34.9% (n=284) in the HIT only group and 33.1% (n=1,288) and 38.2 (n=1,486) in the IVCF only group. No significant difference was noted among groups at either 6 or 12 months (p=0.11 and 0.17, respectively).

Additionally, HIT+IVCF subgroup analyses showed no significant difference in 6- or 12-month mortality between HIT likelihood (p=0.59 and 0.27, respectively) or timing of IVCF placement (p=0.69 and 0.84, respectively). Thromboembolic risk was not significantly different within these two subgroups.

The authors discuss that current guidelines recommend against the routine placement of IVCFs in patients with HIT despite limited comparative data assessing patients with HIT and IVCFs versus either alone. The results of this study suggest that patients with HIT in whom IVCFs are placed are at no higher mortality risk compared to controls nor are they at higher thromboembolic risk compared to previously reported data on patients with either HIT or IVCFs alone.

Commentary

This study compares mortality rates in patients with HIT receiving IVCFs compared to patients with either HIT or IVCF alone as well as evaluates the thromboembolic risk in patients with HIT receiving IVCFs. The authors note that current guidelines are largely based on data describing high rates of thromboembolic events in patients with HIT in whom central venous catheters or IVCFs were placed, but remark that there is limited data assessing the true thromboembolic risk of patients with HIT and IVCF compared to controls. To that end, this study aimed to more accurately characterize the thromboembolic risk and mortality in this population.

The extremely large sample sizes of the control populations, while advantageous for powering the study, did not allow for manual chart review to ensure that diagnostic and procedural codes were accurately assigned in the electronic medical records. In the HIT+IVCF group alone, 9 out of the original 39 cases (23%) were excluded due to miscoding, which raises concern regarding the accuracy of the HIT and IVCF only groups. Additionally, since the control groups were so considerably large, it was not possible for the authors to review all charts to establish thromboembolic risk in each control group. They rightfully discuss that their thromboembolic risk comparison is therefore restricted to previously published data, rather than having an internal comparison. This introduces potential biases between institutional practice patterns, patient populations, and variability over time.

Although generally quite thorough in the evaluation of the HIT+IVCF group, the authors do not mention retrieval rates of IVCFs in either this population or their controls. Given that IVCFs are known to be associated with greater thrombotic risk if not removed, it would have been interesting to see if timing of IVCF removal had any influence on thromboembolic risk or mortality.

Furthermore, although 6- and 12-month follow up periods are relatively long term in relation to duration of thromboembolic risk associated with HIT (which peaks over 14 days), it may also be of benefit to assess longer (3- or 5-year) mortality rates to validate the conclusions over an extended time period. Lastly, the retrospective design has inherent limitations where a prospective study or randomized controlled trial would offer more accurate comparison, although likely not feasible in this relatively small patient population.

The major strength of this study is its large sample size of patients with HIT receiving IVCFs compared to other studies. Their thorough review of laboratory and clinical data to determine likelihood of HIT diagnosis and timing of IVCF placement adds to the comprehensiveness of the morbidity and mortality evaluation. The scope of their discussion also appropriately addresses the limitations of the data and highlights the need for additional research and external validation.

Overall, this study sheds new light on the question of whether IVCF placement should be considered in patients with HIT in which anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated. For patients with HIT and IVCFs, there was no significant difference in thromboembolic risk compared to rates from other studies nor in overall mortality compared to internal controls. These findings challenge current guidelines that recommend against routine placement of IVCFs in patients with HIT; however, outside validation of these results is essential prior to implementing changes in clinical practice.

Post Author

Catherine (Rin) Panick, MD

Resident Physician, Integrated Interventional Radiology

Dotter Interventional Institute

Oregon Health & Science University

@MdPanick

Edited and formatted by @NingchengLi

Interventional Radiology Resident

Dotter Institute, Oregon Health and Science University

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.